Dreams in Youth

Everyone has heard of the Trojan War, and this is astonishing! For three thousand years this story has fascinated humankind, and as a little boy, I found my own passion for the story. As you might expect from a child, I didn’t immediately care much for history, study or difficult books, but I became captivated nonetheless. These stories were just the thing for a young boy who loved the thought of adventure.

First thanks to a video game, and later through books, I learned everything I could about it. The legend of the Trojan War, where to start? I read of a boy raised by shepherds who became a prince. I read of a woman so beautiful that an army set off in ten thousand ships after her when she ran away with this same prince; I read of epic heroes blessed by the gods themselves; I read of a terrible siege that lasted 10 years, where one of the greatest cities on earth was destroyed by a vengeful Greek Army. What I read, the Iliad, was the oldest surviving work of fiction in western literature, and it’s survival has been assured all these millennia because of its breathtaking content. For me, and for the last 150 generations of humans, the great and mythical city of Troy has inspired a passion for the past.

But was it really fiction? Through time, the general feeling about this has changed a lot. In Roman and Greek times, it was taken for granted that the story was true. For instance, we are told that Alexander the Great stopped at the ruins of Troy to pay homage to his ancestor Achilles, who died in the conflict. But by the 19th century, it was generally accepted that the tale of the Trojan War was nothing more than fiction, and this is understandable: the story places Gods and mythical beings in prominent roles; the human characters are over the top; and the sequel to the story, the Odyssey, is among the most exciting fantasy adventures anyone can stumble upon to this day, involving mythical beasts, magic and gods. By the 19th century, the industrial world had moved past this far away world, and held its superstitions with contempt. Troy was nothing more than a fairy tale. Or so it seemed.

Despite this overwhelming prejudice, some nonetheless believed the stories, and staked their reputations and fortunes in order to prove that they were based on fact. In doing this, they would give birth to the science and discipline known today as Archaeology. These characters were exciting in their own right, and when I was a child learning of the Trojan War, my interest shifted from the story of the ancient heroes to that of those moderns who went looking for the ruins of Troy. We might want to call them archaeologists, only they might deserve to be called treasure hunters. At the time, I did not worry so much about these distinctions. I wanted to know if this story was true. I thought that would make it so much better somehow. Could the mythical city of Troy actually be real!?

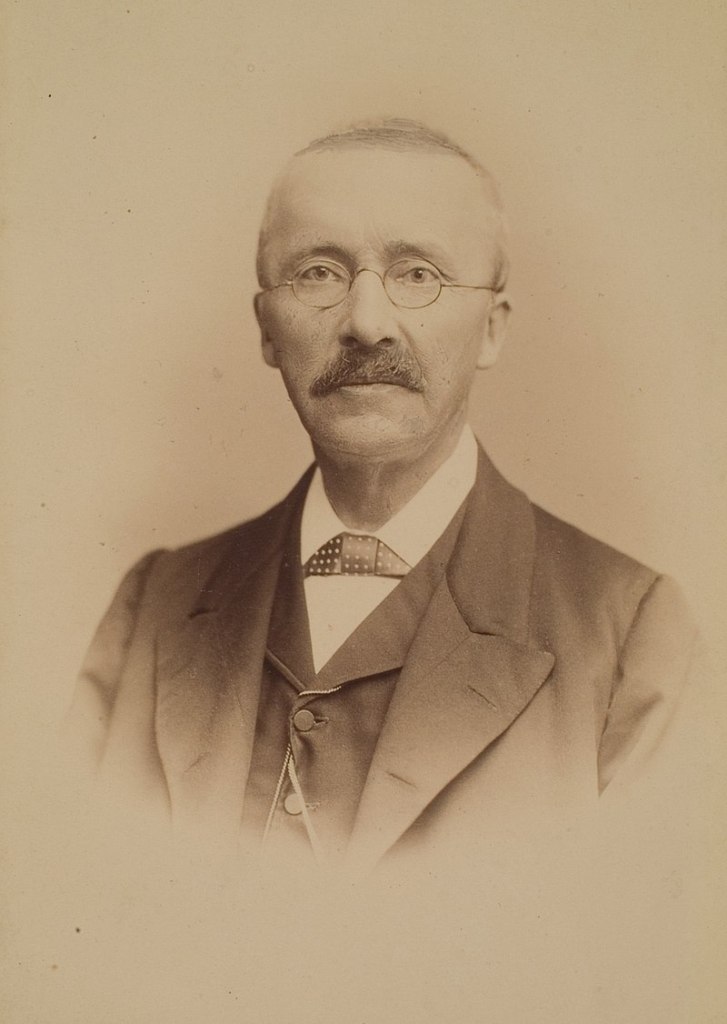

Heinrich Schliemann, Self-Made Millionaire

Heinrich Schliemann believed it was real. Born in 1822 to a poor pastor, in a region of modern day Germany, Schliemann became a fascinating story in his own right. He had very little schooling, and by the age of 14 he had to quit school due to his parents’ poverty. For the remainder of his adolescence, he got a job, apprenticing to a grocer. Schliemann tells us that from a very young age, he too grew a fond appreciation for the Trojan Myth.

Eventually, Schliemann’s promise of a comfortable life as grocer was interrupted by the fortunes of life; he was injured. He had to quit his job, and he took new one as a cabin boy on a steamship heading to Venezuela. After twelve days on board, his second prospective career was also cut short as the ship sank in a storm, and a 19-year old Schliemann had to start over from the shores of the Netherlands.

From this point on, a pattern emerged in Schliemann’s life. He exemplified the driven man who would try anything and everything to get rich. He took every risk, traveled across oceans at hints of opportunities, started businesses, wrote books and learned languages everywhere. Schliemann was apparently quite the people person; charismatic, very talented, and very intelligent. His worldly abilities, as well as his ability to adapt socially, is best demonstrated by his grasp of many languages.

After having been sent to Russia by an import/export firm as their general agent in charge of negotiation and representation, Schliemann taught himself Russian and Greek. In doing so, he developed a system of learning languages by which he claimed he could learn a new language in just six weeks. That’s a bold claim, but by the end of Schliemann’s life, he supposedly could converse in English, French, Dutch, Spanish, Portuguese, Swedish, Polish, Italian, Greek, Latin, Russian, Arabic, and Turkish as well as German. Apparently, he would also write in his diary in whatever local language he was immersed.

Schliemann would become fabulously wealthy through his life. He had done well in Russia, but he got his first major break at the age of 29, when he got news of his brother’s death. His brother had started an investment business that speculated in the California gold fields, and had just gotten it running when he died. Heinrich left Russia for America, and took over his brother’s business. Within a year, he had turned a major profit, and was even made an American citizen when California was made the 31st U.S. State. After a year, he would sell his business and return to Russia in 1852 now in his thirties. He does not appear to have had business interests awaiting him in Russia, but perhaps he simply felt more at home in Europe and Russia than in the American Frontier.

In Russia, he married his first wife, with whom he had three children. It would be an unhappy marriage, but the timing of his return was perfect; he would make a lot of money in the next few years. He first cornered the market of indigo dye, a very lucrative business, and then became a military contractor for the Russian Government during the Crimean War of 1854-56, where he held the market for saltpeter, sulfur, and lead, all constituents of ammunition, which is naturally in big demand in wartime. By the end of the war, Schliemann was 34, and rich enough to never work again. He kept at it for another decade, but eventually he left his businesses to run themselves. As we will see, he had other interests.

Millionaire Eccentric

In 1866, at 44 years old, Schliemann went back to school. Like many who are deprived of education as children, Schliemann probably saw it as a privilege he needed to have. He enrolled at the prestigious Sorbonne University in Paris, and took classes in Poetry, French, and Greek and Arabic philosophy. But spending time in school was perhaps not the end all and be all that Schliemann had hoped it would be. This is a man who did not smoke or drink all his life. He swam in cold water everyday because he believed it was good for his health. He wanted to do more and more and more! As it was, his studying reinvigorated his childhood interest in the Trojan myth, and eventually he became consumed by it.

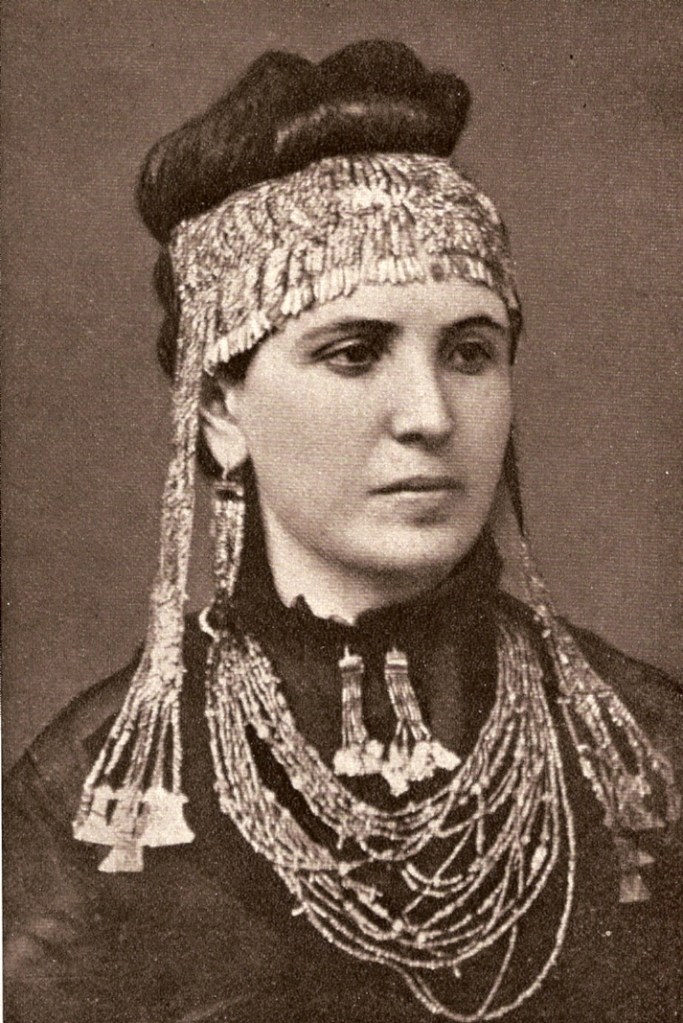

All the ambition and drive that had led this man across the world was now focused on discovering the legendary city of Troy. He believed it was all true, and he had sworn to find the lost city. He set up a base of operations for himself in Athens, which quickly became his favorite city in the world. He took the classical lore of the place more seriously than did the locals and would even implicate himself in politics to lobby for the preservation of the purity of ancient sites. He would make himself enemies by having medieval structures destroyed on the Acropolis because he believed that only ancient Greek architecture should be allowed. He even decided that he needed a new wife, and that she had to be Greek. He wanted a companion to share in the thrill he felt at discovering the Greek past. So he asked a friend for help introducing him to suitable women in Athens, and was eventually introduced to a young girl named Sophia. She was 17, and he was 47. Despite the large age gap between them, she happily agreed to marry him. He asked her at once why she had agreed to marry him, since he was so old and all; to which she immediately replied that it was because he was rich. Somehow, they were honestly happily married.

Schliemann’s belief was that the Iliad was a historical document based upon truth, and not a fantasy. In this way, he was going against all the credible historians of his time. His reasons for believing this are unclear, but if anything about Schliemann should be obvious by now, it is that he did not mind going against the grain, and was exceedingly impulsive.

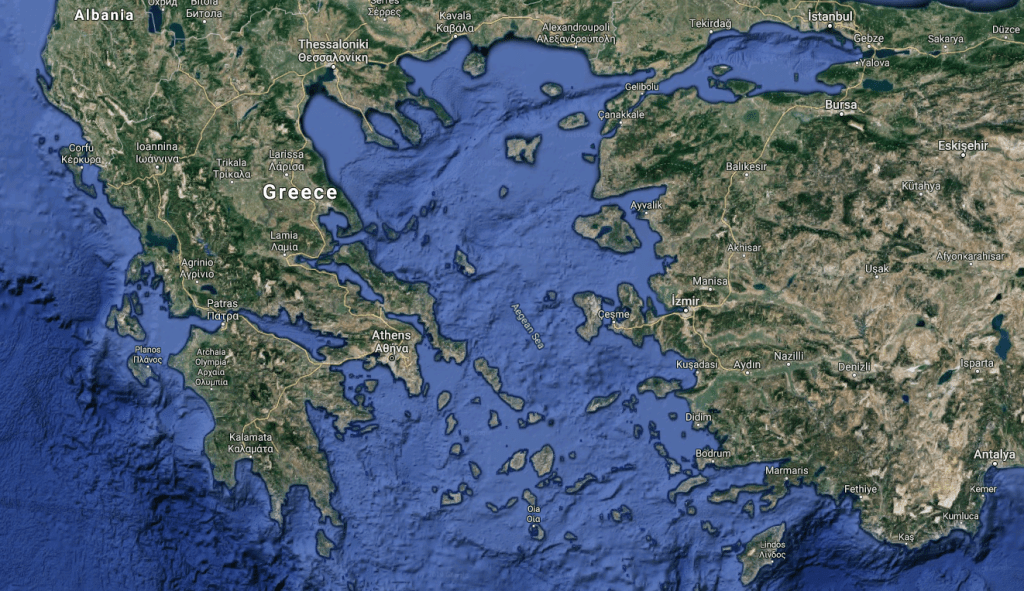

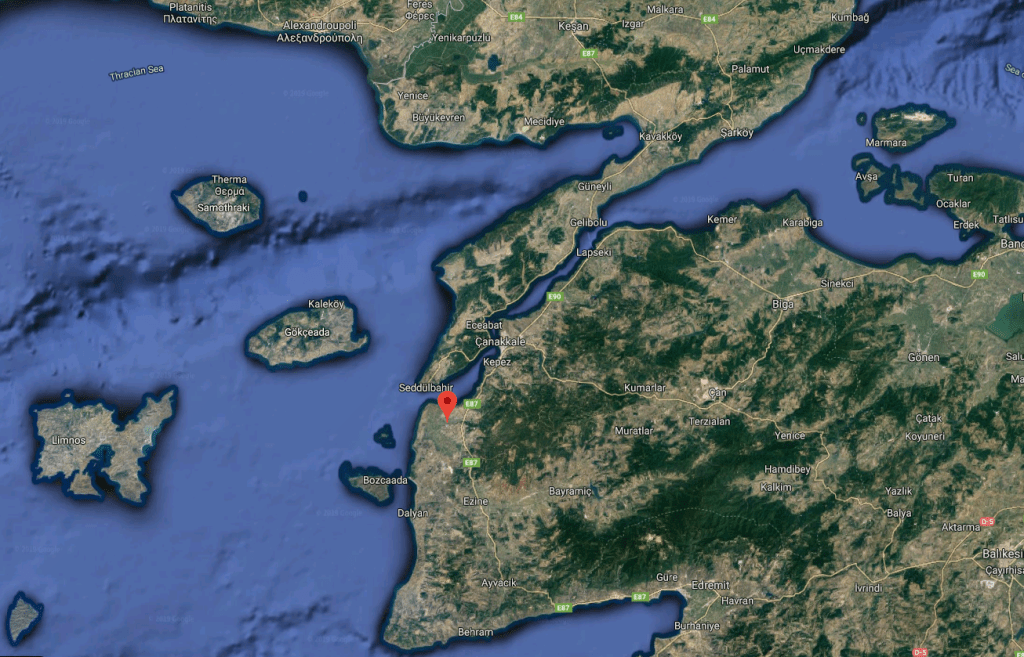

Eventually, he left for Troy, employing as his guide the verses of Homer’s Iliad. He looked in the book for descriptions of locations, and tried to find them in the world. He went to Turkey, since the Iliad situates the Trojan city on the eastern side of the gates of the Hellespont. There, the Aegean Sea situated between modern day Turkey and Greece slims down to a narrow passage which winds north, into the Dardanelles. Accordingly, at the mouth of the Dardanelles, Schliemann went looking for his city.

At first Schliemann was unsuccessful. The book placed the city atop a hill, overlooking the Hellespont. After digging in several locations, Schliemann was going nowhere. Even if the book could have provided useful information once upon a time, the geography had changed dramatically over the three thousand years that had past. The fact that geography was dynamic was not necessarily well understood at that time, and he had no luck. However, after beginning his search, a man named Frank Calvert introduced himself to Schliemann. Calvert and his brother had been living in the Ottoman Empire for a long time, where they worked as consuls for Britain. Frank Calvert had already discovered the legendary city of Troy.

Calvert had determined that the city was located on a hill named Hissarlik, and in 1863 he had excavated a temple on the site to prove his point. Despite being wealthy enough to purchase the majority of the land around Hissarlik, he did not have the leverage necessary to begin major excavations. And to be clear, excavating old sites suspected of harboring hidden ruins was not the norm at that time.

Schliemann would rectify this situation. He reached a deal with the Ottoman Empire, by which it was determined that if any treasure was found, it would be split between the Ottomans and himself. The generous nature of such a deal on the part of the Ottomans just goes to show how little they expected him to find. Schliemann accepted this heartily, but did so with fingers crossed.

The Destroyer

Discoveries were slow to come. He was not finding what he was looking for at Troy, no treasure at all. Even worst, he and Calvert could tell that the Homeric Troy which interested them was still deeper than the ruins they were excavating. Schliemann therefore opted for a new method. With a large force of laborers, Schliemann dug a large trench strait through the hill, removing all that he found until he thought he had reached the Homeric period of habitation.

This trench is an archaeologist’s worst nightmare. He destroyed everything he passed over. Threw out god knows what pieces of evidence might have instructed more educated archaeologists. I have to admit, when I visited Troy, this trench stunned me.

When you first arrive at the site today, you walk down into a corridor located between two huge, thick, intact walls that tower over you. Later excavated by Wilhelm Dörpfel, these walls are more than three thousand years old and blow you away. They protected the old palace, and as you walk around the walls to the palace entrance, you pass from a breathtaking sequence of ancient architecture to a broken, unrecognizable pile of debris. As you walk into the sections that Schliemann excavated himself, you walk into a sad place of broken history. I never had a bad feeling for my childhood hero Schliemann before I stumbled upon that sight. Calvert and Schliemann fell out over this trench when Calvert publicly criticized Schliemann for the first time. As much as I admire Schliemann, I respect the story of Troy more, and I wish another had financed it’s excavation.

What he was trying to get at however is a common problem in archaeology. As time goes by, layers of homogeneous sedimentation accumulate one atop another in a uniform manner. This is a geographical principle named stratigraphy; it states that as you dig down into the earth, you will come across distinct layers of soil, like many sheets of a bed layered on top of each other. If you find something in one layer, and another thing in a different layer, then you know that they are from two different time periods. Herein lies the problem: if you have 2000 years of occupation in one place, the oldest stuff is beneath the newest stuff. Therefore, if you want to get at the oldest stuff, you will have 1999 years of history in your way.

In the late 19th century, the field of geology was only beginning to be codified, but Schliemann and Calvert understood that their first findings near the surface corresponded to later periods of Hellenistic and Roman occupation. They could easily tell from the architecture, building methods and style that they found. They understood that if this site was indeed Troy, they had to go bellow these later constructions. Today, this would have been achieved slowly, methodically, and every stone and artifact found would be documented and it’s location of discovery would be shown on a precise grid map of the excavation site, and sonar and radar and ultrasound technology would have probed the ground searching for appropriate dig locations, and would have informed of probable building locations, and the meticulous process would have permitted the discovering, and maybe even understanding of an ancient past! Of course, by stating that today technology makes archaeology far superior, is not meant to discredit early efforts at archaeology. It is rather that Schliemann’s work is more comparable to fishing with dynamite, and he is hated for this in historical circles.

I have to admit, as a child, and even all the way up to my visiting Troy in August 2019, I didn’t much care. I had heard others say these things about him, but I thought Schliemann had to be forgiven for these trespasses for a number of reasons that still hold significant weight. First, archaeology was not some well understood science as it is today. There was no standard method of excavation. Even Arthur Evans, an archeologist who was contemporary to Schliemann destroyed any future possibility for excavation in his Cretan sites by reconstructing ancient buildings in their original location! He had no idea how they should look! He only knew the layout of their foundation! This is also a nightmare! Schliemann, Evans, they were all just learning. Then there was the notion that Schliemann was bleeding money here, and couldn’t possibly know if he was in fact spending his money wisely. Could he truly KNOW that he was at Troy? At the end of the day, Schliemann was among the first private sponsors of Archaeology, so we should give the guy a break! I thought Schliemann’s impatience could be justified, and moreover, the work conditions were bad for everyone. Malaria was a serious problem, as was the heat, cold and nature of the work. It was clearly not an ideal working environment, and anyone would have wanted to get the job done as soon as possible.

This brings us to the question; what did Schliemann really want to get out of finding Troy? What was his reason for spending so much time and money on this? On the one hand, there is the simple story of fascination we began with, but this seems hard to digest at this point. What I think, is that Schliemann wanted to be famous. Not famous like normal celebrities today; he wanted to be remembered by history. This naturally strikes us as megalomaniacal, but it make’s me think of a story from the Iliad, in which the great hero Achilles is told a prophecy. He is told that if he is to go to Troy, he will die, but be remembered for all eternity as a great hero. Alternatively, if he is to stay away from Troy, he would lead a long and happy life of anonymity. Achilles chose an early death and eternal fame. Since reading that story, that part has intrigued me about what this meant about the average person, but Schliemann appears to have shared Achilles’ desires. We are after all talking about him now.

After all this however, we are still left with Schliemann’s destruction. Ever since Schliemann plowed through Hissarlik, archaeologists have struggled and strained to put things right at Troy. Meticulous reconstruction of sections hurriedly destroyed by Schliemann has been undertaken ever since. For one reason or another, it has been mainly Germans that led excavations at Troy, and when I visited, I was there with a friend from Germany. He communicated to me that these German archaeologists must have lived with so much shame at the handiwork of one of their countrymen upon one of the world’s most famous archaeological sites.

Stolen Treasure

Somehow, still to this day Calvert’s name barely comes up, but it is he who pointed Schliemann to the correct location, and who assisted the amateurish Schliemann at the beginning of his archaeological career.

Clearly, Schliemann had a dark side. The sort of ambition that fueled Schliemann’s rise is very often found harboring a flexible morality. For starters, Schliemann would have made a fine politician considering his relationship with truth. Throughout his life, Schliemann was called a liar, fabricator, con artist, and a great many things he said were later refuted. He has one of the most confusing Wikipedia pages you might find, and all the contradictory facts are supported by citations. I have three books about him that contradict one another on a variety of facts. He wrote a piece in 1851 pretending to be an eyewitness to the San Francisco Fire when in fact he was nearly a hundred miles away in Sacramento. He didn’t even get the date of the fire right. He might have lied about when and how he got his American Citizenship. He definitely lied to the city of Indianapolis in 1868 when he moved there to take advantage of their liberal divorce laws. He claimed he would settle in Indianapolis and bring all of his assets if he could get a divorce, then left for Athens, never to return, the moment the divorce was finalized.

His career as a liar was only getting warmed up at this point. Though grateful to Calvert, Schliemann never shared an ounce of success with him. Calvert had submitted a paper in 1865, before Schliemann was even on the scene, making a case for his discovery of Troy, but he was apparently not nearly as loud as Schliemann was, when he claimed all the credit for the discovery in 1868. On first inspection, Schliemann seems a brilliant mind capable of making money and connections in uncertain times, and probe a little deeper and his abundant repertoire of lies inevitably makes him look slimy.

His character is best demonstrated by the following events. On a certain day, all the efforts and money that Schliemann had invested in Troy payed off. Having dug the previously mentioned trench, Schliemann thought that they were at the level corresponding to Homeric Troy, and there they literally struck gold. Schliemann sent the workers home and excavated the remainder of the section himself. He gathered all the gold, and hid it in the bottom of food baskets. After a few months, he took a boat back to Athens, and smuggled all the treasure to Greece with him.

This was a crime, Schliemann was now by definition a treasure hunter and a thief. He could no longer call himself an archaeologist. Any authentic desire he might have had to be a respected student and authority on history was dashed in this moment. He showed in this action that he was in it for the publicity, and now he had his ticket to fame. He publicized his discoveries every which way he knew; he called it Priam’s Treasure, after the Trojan King in the Iliad; he even had his wife wear the treasure at public high society events. He kept the treasure for a time, and took the following photo of his wife Sophia adorned in gold jewelry thousands of years old.

Clearly, the main ethical problem with treasure hunters is that they are more concerned with extracting specific objects of value than with the development of the historical record. Normally their goal is to bring artifacts to sale on the market (or black market). Archaeologists work like crime scene investigators, and consider every aspect of the areas that they excavate. They want to understand the nature of the items they find, of the location and orientation of these items. Like anyone taking something from a crime scene before an investigator shows up, treasure hunters can really ruin an archaeologist’s ability to learn from a site. Beyond that, if ancient items are important because of the way they tie us to our past, it seems right that they should primarily belong in publicly owned collections located in the region of discovery, and not be hidden away in foreign and private collections. Moreover, Calvert and others at the time criticized Schliemann’s actions on the basis that in the future, foreign authorities would never trust the word of an archaeologist again. In this way, he rightly argued that Schliemann’s publicized treasure hunting was creating obstacles to attaining knowledge about the past.

His theft led to the Turkish government revoking his digging permits, and forbidding him from returning to Turkey, though these decisions would be overturned in the future. He defended his theft to the general public by stating that he was protecting the treasure from corrupt Ottoman officials. This might not be as silly as it seems on the surface, but would certainly have be well received by the general European public of the time. He would eventually take his cue from Indiana Jones by donating the treasure to a museum. Unfortunately for Greece or Turkey, Schliemann appears to have made a deal with the German University of Pergamon in Berlin, whereby he gave them the treasure in exchange for a Ph.D.

Schliemann had wanted to be recognized as the best authority on Troy, and ultimately wanted to be admired by those professors of history that he looked up to. He wanted to be the living breathing image that people conjured up when they thought of Troy. The universities however, couldn’t stand him, and were his harshest critics. They hated that this outsider, who had barely spent any time at all in an institute of higher learning was telling them that he had made this great discovery about the past. Newspapers published whirlwinds of letters from Schliemann defending his discoveries, and professors debunking successfully and unsuccessful his so-called theories. It never really ended, but esoteric debates about history have largely faded from mainstream news.

The treasure remained in the Pergamon museum until it went missing in World War II. No one seemed to know of it’s whereabouts until 1993, when the treasure turned up at the Pushkin Museum in Moscow. Germany, Greece, and Turkey now claim the treasure, but Russia is unlikely to give it up anytime soon; in 1998 they legalized the possession of war plunder taken from German cities in World War II. That same law prevents Russian authorities to enact restitutions.

The Birth of Archaeology

In any event, Schliemann had not found Priam’s treasure. It could not be since he found it too deep. Recalling our discussion of stratigraphy, Schliemann had dug to one of the deepest layers to find the treasure. But this layer was not the Homeric Troy. Today we understand that the site of Troy has been occupied by a number urban iterations. It was first occupied by humans around 5000 years ago. The lowest layer of excavation, Troy I, as it is now known, is made up of a small citadel that was used from 3000-2600B.C. Troy II, the next urban iteration was built on top of Troy I, and features a larger elevated citadel, surrounded by a sprawling lower town beneath. This second city is considered to have existed between 2600–2250 BC, some 4600-4250 years ago. Priam’s Treasure was found in this layer, and years after it’s discovery, Schliemann’s assistant, a man named Wilhelm Dörpfeld, declared that Schliemann had been wrong. This created a fuss, but Schliemann eventually admitted that Dörpfeld was right.

Dörpfeld would become an important component in this story. He was an architect by training, but immediately after graduating went working in Athens, participating in ancient excavations. His talent was recognized, and he would eventually be put in charge of those excavations. Archaeology, however, was never a lucrative job, and Dörpfeld was a poor man who had borrowed money to become educated. He went back to Germany, got married, and was looking for a job as an architect when he fortuitously met Schliemann. Schliemann caught him at just the right time, and probably persuaded Dörpfeld to follow his dreams with ease. Dörpfeld would be an asset. He was meticulous, worried and patient, and less interested in fame than Schliemann.

Schliemann would give Dörpfeld control over Troy, and trust him to continue excavations. He would develop the theory of stratigraphy we elaborated earlier at Troy, and described all past and future excavations he undertook at Troy according to it. After Schliemann’s sudden death in 1890, Sophia Schliemann would pay for Dörpfeld to continue the excavations, believing it was what her husband would have wanted, and perhaps she also cared herself. Dörpfeld described 9 layers, and though some of the details he elaborated would be found imprecise, his general theory was validated by the credentialed archaeologist Carl Blegen in the 1930s as well as by all others that have excavated Troy since then. Schliemann has been called the father of Archaeology, but I now disagree. If anyone deserves that title, it is the assistant Dörpfeld. Thanks to him, scientific sense was made of Schliemann’s excavations, and many sites were saved from his destructive methods. A strict method of digging and of note taking was established under Dörpfeld’s leadership, whereby sites were to be understood, not plundered until they yielded grand artifacts. In fact, though this title is not given to him on his English Wikipedia page, it is given in his German Wikipedia page as of September 2019.

It is worth describing the 9 strata of Troy, to demonstrate the power of Archaeology. Troy I and II have already been described briefly, but it is important to note that it is visible that Troy I was destroyed in a fire, and that Troy II was built by the same people on the ruins of the previous iteration. This statement can be validated by reference to architecture, building methods, types of pottery found, and it can be extrapolated to indicate that the fire that destroyed Troy I was accidental. Troy II on the other hand was probably destroyed by war. Marks of fire are also visible at the end of this strata, as well as evidence of conflict, such as arrow heads in walls and etc. Troy III, IV and V (2300B.C. – 1700B.C.) each got larger than the previous iteration, with the citadel remaining mostly the same size. The walls got higher and the outer city walls spread further and further.

Troy VI is contained within a strata that places it between 1700-1250 B.C. This city was the largest iteration and most grandiose yet. The city was clearly rich, and artifacts collected in this layer have their provenance as far as from the island of Crete. This city would be destroyed by an earthquake in 1250 B.C. and would be rebuilt immediately after by the same population. Throughout these iterations, the people that did the building often reused materials from older sites while building new ones. In this way, certain layers are depleted of evidence, and can reveal very little. As seen in the image below, Troy II is shown in Yellow. Despite being a very old layer, it is mostly intact since the citadel walls created in this period would not move or be destroyed for the following millennia. As such, this layer was always added to, not recycled, as is the case for layers III, IV and V. In those layers, new building methods and styles were elaborated, by which old buildings were torn down and rebuilt using most of the old materials. As such, little remains of these iterations.

Troy VIIa is where it gets interesting. It is contained between 1250-1180B.C. It was destroyed by fire, it was organized to hold more supplies than any other Troy, and arrowheads were found planted in the city walls. It is also the only strata in which human remains were found. Moreover, these remains were fire-damaged, and not intentionally buried, but were found in what looked like random places. This was Homer’s Troy, the city that was besieged by the Greeks for 10 years, if the story is exact. The vast storage space in the city was meant as an insurance during threat, when it was not possible to cultivate or forage. Troy VIIb is contained between 1180-1000B.C., and it was occupied by the survivors of the siege. They lived in haunted ruins, surrounded by ghosts of a glorious past. Troy VIII and IX were later Hellenistic and Roman settlements, respectively, and these layers are contained between 1000 B.C. and 600 A.D. In fact, before the Roman Emperor Constantine declared that Constantinople, modern day Istanbul, was to be the new capital of the Roman Empire, he had first considered the city of Troy.

As Nick McCarthy wrote, archaeology requires money, patience, and the willingness to seek out a variety of views to explain findings. Schliemann only had one of these three virtues. But I would argue that Schliemann had fourth virtue which makes him an important cog in the creation of archaeology; Schliemann reminded the world that the stories of our past are more often than not based in some kind of truth. From biblical stories involving massive floods, to ancient Greek epics about divinely ordained war, to who knows what else; these stories have been imperfectly passed down from true event, to word of mouth, to pen and paper.

As we have previously mentioned, Calvert had publicized his discovery of Troy years before Schliemann was ever invested in its search. The fact that no one listened, and that it didn’t become big news says a lot about Schliemann. It is rare that people today become uproarious and excited about the ancient world, but with Schliemann around they did. The newspapers really were all covering his story. Everyone knew of him, of his discovery at Troy, and of the fierce debate that raged between him and academics. He was certainly a genius of communication, marketing and publicity. It seems obvious that the discipline of archaeology could not have found a serious place in academia without Schliemann rubbing their nose in his “amateur” discoveries. Moreover, Schliemann’s publicity would inspire countless youths to enter the field of history. He made it exciting. I personally know archaeologists who found their passions reading about Schliemann.

I myself almost became one because of him. It would take me time, but I would later realized that what I was actually in love with that the cliché of the archaeologist explorer, not so much the actual doing of science. I guess I had to grow up; but after all of this, that’s the reason I still like Schliemann. He doesn’t seem to have ever grown up or listened when people told him he couldn’t do something. Seems like he did everything he wanted. I began this text believing I was about to write about the story of the discovery of Troy, but by now I realize that what I’ve laid out is my internal debate about one of my childhood heroes, Heinrich Schliemann. So be it, I hope that it may be interest to others to know how Schliemann has captivated me.

At Troy, Homer created the character of the noble ancient hero. In the same place, Schliemann created one of it’s modern day counterparts in the archaeologist explorer. It seems that as humans, we always need some kind of hero in our narratives. Let this be the moral of this story; give people facts and events, and they probably wont care; but fit your actions in a narrative with heroes and villains, and they will listen. In those two lines is written the story of every successful and unsuccessful political campaign, war and civilization. We are all tied together by the narratives we write about ourselves, and the victor is he who’s narrative is taken by others as their own. Schliemann was a master of story telling, and he used this skill to gain fortune and fame. Let us not forget that he had Homer as his favorite teacher.

The collapse of civilization has occurred regularly in history; the Bronze Age that these Greeks and Trojans fought in would collapse soon after the story’s events, and it was so bad that the Greeks forgot how to write. Yet we still have this story, which we now know is based in truth. I believe that by promoting his controversial discovery at Troy, in the face of an establishment that ridiculed his efforts, we were taught to marvel when looking back, for our ancestors have been through hell and back to create the world we have now. Our ancestors have endured war, famines, crises, all to be forgotten, and for however brief a time, Schliemann brought one of their stories to the fore of our existence. He remains inexorably attached to Troy, and will go down in history as a piece of the story of the Trojan War, to be judged a hero or a crook by generations to come.

References

- McCarty, Nick. Troy, The Myth and Reality behind the Epic Legend. Carlton Publishing Group and Barns & Nobles Inc. New York. 2004

Available : Troy: The Myth and Reality Behind the World’s Epic Legend by Nick McCarthy (2004-04-01)

- Aslan, Rüstem. Troy, City of Mythology and Archaeology; Unesco World Heritage Site. Içdas. 2nd Edition. Istanbul. 2018.

Available : I can’t find an online link yet.

A variety of other sources were used, taken from various Wikipedia pages.

Other interesting sources below.

Irving Stone’s Greek Treasure. A novel about Heinrich Schliemann.